Justice Sector Assessment

One

of the site visits of judges from the United States participating

in the International Judicial Academy’s annual seminar

on international law and international courts in The Hague,

Netherlands is the Hague Conference on Private International

Law. Most of the American judges who have attended the

four IJA seminars (now numbering over 100 alumni/alumnae)

have either been totally ignorant about the Conference

or only vaguely familiar with it. In my conversations

with other judges in the U.S. about the work of the Hague

Conference, the most frequent response is: “I have never

heard of it.”

One

of the site visits of judges from the United States participating

in the International Judicial Academy’s annual seminar

on international law and international courts in The Hague,

Netherlands is the Hague Conference on Private International

Law. Most of the American judges who have attended the

four IJA seminars (now numbering over 100 alumni/alumnae)

have either been totally ignorant about the Conference

or only vaguely familiar with it. In my conversations

with other judges in the U.S. about the work of the Hague

Conference, the most frequent response is: “I have never

heard of it.”

This situation of almost total ignorance about the Conference, its purposes, functions, and activities probably exists among judges in a number of countries around the world. The information deficit is serious, because the activities of the Hague Conference and the international conventions that it administers are extremely valuable in today’s world, in that they can affect, not nations, but “the lives of their citizens, private and commercial, in cross border relationships and transactions” in many different, important sectors. As a monograph on the Conference states:

Although our world is increasingl;y interconnected, it is still composed of a great variety of legal systems, reflecting different traditions of private and commercial relationships. When people cross borders or act in a country other than their own, these differences may unexpectedly complicate or even frustrate their actions. For example, in some countries marriages take place according to various religious forms, while other countries require a civil marriage; will either system give effect to the other’s form of marriage? Two cars collide in Austria, injuring the passengers, all of whom are Turks; will Austrian or Turkish law apply in deciding damages or compensation? A patent certificate issued in California must be produced for official use in Russia; is there a way to avoid cumbersome legalisation formalities? A London trustee wishes to acquire property; can he do so in Italy where trusts do not exist? A Moroccan-Dutch coiuple separates and the father takes their children to Morocco; does the wife have a remedy if her custody rights are ignored?

The Hague Conference exists because of the existence of different legal systems; it exists because of the differences of specific legal treatment of various legal subjects in those different legal systems. It exists to resolve the kinds of issues and answer the kinds of questions raised and posed in the above examples. The mission of the Hague Conference, as stated in the aforementioned monograph, is “to develop and service frameworks of multilateral legal instruments which, despite the differences in legal systems, will allow individuals as well as companies to enjoy a high degree of legal security.”

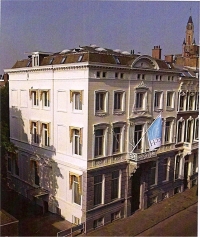

The Hague Conference on Private International Law, as a permanent organization in the Hague, is derived from a series of private international law conferences held in The Hague beginning in 1893. The inspiration for the convening of such a conference in Europe was a diplomatic conference involving seven South American countries in Montevideo, Uruguay in 1889. The initial European conferences actually occurred because of the interest and leadership of T.M.C. Asser, a Dutch national who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1911 for his work in this area.

Asser organized additional conferences in The Hague on private international law in 1894, 1900 and 1904. These four initial conferences resulted in seven conventions covering civil procedure; marriage; divorce and separation; guardianship of minors; effects of marriage on rights and duties of spouses; and deprivation of civil rights.

After World War II, the seventh Hague Conference in 1951 created a permanent organization, now officially known as The Hague Conference on Private International Law. Sixteen states signed the original implementing statute. By 1965 that number had grown to 23, and in 2007 the member states totaled 66.

The Hague Conference’s organic statute provides for diplomatic conferences every four years. The conferences are held in the Peace Palace in the Hague (home of the International Court of Justice). A small permanent secretariat plans and conducts the conferences. The official languages of the Conference are English and French. One of the challenges facing the Conference during its years of growth has been to accommodate the principles and practices of civil law (primarily European) countries with those of common law countries. On this issue, the monograph states:

With the growth of its membership, bridging the gap between common law and civil law systems became an important challenge for the Hague Conference. The concept of “habitual residence” became prominent as a connecting factor in international situations, both in order to determine which law to apply and which court should have jurisdiction. This concept was adopted at the expense of both the nationality principle, so popular during the first generation of Hague Conventions, and the principle of domicile, the primary connecting factor in the common law jurisdiction. Techniques were found to accommodate differences between civil and common law systems for the service of process abroad and for the taking of evidence abroad; to reconcile different conceptions of the succession of estates of deceased persons and the administration of such estates; and to recognise the institution of the trust, widely used in the common law world but practically unknown in civil law systems.

The Conference, under a revised statute, is also authorized to admit regional organizations, which it did in 2007 by admitting the European Union. This admission was in addition to the prior admission of all of the EU’s 27 member states. It has also, since 1951, adopted 36 conventions in three major areas: international legal co-operation and litigation, international commercial and finance law, and international family and property relations.

Even though a country may have ratified one or more of the conventions, for a convention to acquire the force of law, it “must pass through the constitutional procedures of that country.” For a country that has not ratified a particular convention, that convention may still be beneficial to it, in that the particular country can simply incorporate all or part of the convention’s provisions into its own domestic law.

One of the most successful conventions of the Conference has been the Child Abduction Convention, which addresses the prevention and correction of wrongful removal of a child from a particular country. Another successful convention, the Intercountry Adoption Convention, sets “universal standards for the conditions that must be fulfilled before a child may be adopted abroad, as well as providing the machinery for international cooperation in light of these standards.”

A recent development, of particular interest to judges around the world, is the establishment within the Hague Conference in 2007 of an International Centre for Judicial Studies and Technical Assistance. This center provides information and assistance to judges and other legal professionals who must deal in one or more areas addressed by the private international law conventions administered by the Hague Conference.

Most attention in the media is given to issues of public international law (on relations between states) and international civil and criminal courts. But the work of the Hague Conference on Private International Law provides an admirable example of how another type of international law contributes to a peaceful world by encouraging cooperation among nations to assist their citizens, individual or corporate, in many affairs of life which can affect so many people.

By Dr. James G. Apple, Editor-in-Chief, International Judicial Monitor, and President, International Judicial Academy.