Justice Sector Assessment

| The Long

Winding Road: Judicial Sector Reform in |

Well-functioning

justice sector institutions, a key pillar of good governance,

are not just guarantors of human rights and freedom in any

country they are also key to creating a favorable investment

climate and advancing economic development. Good laws and

regulations alone, however, do not ensure that the justice

sector functions well, with integrity and independently,

and without undue outside influences. Like any organization,

courts, prosecutors’ offices and other justice agencies

need to have the resources, need to be managed appropriately

to be effective, and supported by a leadership and society

interested in ensuring its proper functioning within a democratic

environment.

Well-functioning

justice sector institutions, a key pillar of good governance,

are not just guarantors of human rights and freedom in any

country they are also key to creating a favorable investment

climate and advancing economic development. Good laws and

regulations alone, however, do not ensure that the justice

sector functions well, with integrity and independently,

and without undue outside influences. Like any organization,

courts, prosecutors’ offices and other justice agencies

need to have the resources, need to be managed appropriately

to be effective, and supported by a leadership and society

interested in ensuring its proper functioning within a democratic

environment.

Western democracies continue to refine and revise the meaning of good governance and its translation into justice sector operations as their societies change. Evolving democracies are facing even tougher challenges in this process. They are challenged to develop a vision, define their essence and translate it into organizational and societal structures that can reflect and uphold the changing values of these societies while facing tremendous economic and political challenges within their country that are increasingly shaped by global economic and political realities.

| |

| Mongolia, landlocked, wedged between Russia and China |

One country that has struggled and done relatively well in

a very difficult transition process is Mongolia, a huge, land locked country

with few people, extreme economic challenges, wedged between

While the Mongolian legal system today looks quite like the German legal system, some elements from common law systems have been introduces, such as inclusion of some adversarial processes, an unusual commitment to strong judicial branch administration and independence of the courts and prosecutors’ services form the ministry of justice. These new concepts still need to evolve, a difficult process particularly since the justice system shares the overall transition challenges with rest of the government and society.

The difficult economic situation has reduced government spending in all sectors. While inflation and unemployment increased, the social welfare system and other public services, once of first-world standards, almost disintegrated, leaving rising numbers of the poor with no safety net. The slowly evolving economy and privatization presented other challenges. Higher caseloads and increasingly complex cases before criminal and civil courts escalated the demands on an already strapped justice system. Under these conditions, it is remarkable that the justice system has been able to function to the extent it has, even though many remain discontent that the rule of law is not well established, and critics often question the fairness of the justice system.

| |

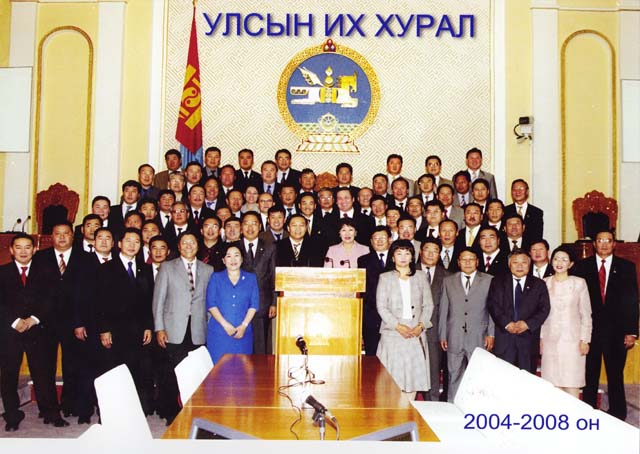

| Mongolia's Ikh Hural 2004-2008 A high proportion of women in the judiciary, but low proportion in the Great Hural governing body indicates judicial profession’s low prestige in Mongolia. |

While public perception of the judiciary has improved many still perceive that judges favor relatives and support their native regions, and are not well-versed in many substantive areas of the law (particularly economic law and human rights). Critics point out that the high proportion of women in the judiciary (approximately 70% in the countryside and 50% in Ulaanbaatar) indicates the profession’s low prestige. Human rights activists cite the lack of effective representation in court, abusive police treatment of the accused, seemingly arbitrary arrest and detention practices, and horrendous prison conditions.

As

in other sectors, the legal and structural reforms have

been so significant and fast that the judicial system has

difficulties fully absorbing all the new laws, standards,

and responding to the new demands on them. Under the former

Soviet style system, the position of

Despite significant international support to training judges and others in the justice system skills are still lacking and government and private lawyers have yet to adapt to and fully embrace the new system. This indicates that existing legal training may have created abstract knowledge of the law, but not the capacity to apply it in a changed system. Moreover, justice system employees, including judges, while generally well educated, often lack the knowledge and resources to succeed under the new system. They are still hampered by significant underfunding, translating into low salaries, lack of even basic resources and a crumbling infrastructure.

Nevertheless, a number of promising changes can be observed.

Particularly in comparison to other countries in region,

the Mongolian courts and prosecutors’ services are well

on their way to becoming professional institutions that

protect the rights of the people and uphold the rule of

law. There is real commitment from the judicial leadership

to make the needed adjustments despite the many challenges.

International assistance for justice sector reform, particularly

from the

Starting the same year, another USAID funded project, the Mongolia Judicial Reform Project (JRP), also administered by NCSC, has since supported the implementation of this reform plan. While select law reform activities continue as the understanding of human rights issues and the need for transparence and accountability increases, and as societal and economic demands for responsive justice sector services grow, the initial focus of the assistance was on developing the infrastructure, basic legal understanding and capacities within the judicial sector and outside. This concentration eventually shifted to developing a cadre of professionals that embrace change and that have not just the legal but also organizational and management skills and a commitment to creating efficient organizations that serve the public. This process of changing fundamental attitudes and understanding is the most difficult in any country and requires time.

| |

| Mongolia Judicial Reform Project is underway |

Many aspects of the Strategic Plan have been implemented — but not all. Today all courts and most prosecutors’ offices are automated, case management software assists in tracking cases, managing caseloads and providing management information. All courts have public access terminals where everyone can check on the status and outcome of a case. Courtrooms have been redesigned and policies changed to provide for more equality among the parties and for public access, particularly media access to the courts. All judges and prosecutors have access to the latest laws, many via an electronic information network.

Control

over the General Council of Courts, the governing and administrative

body for all courts in

Prosecutors are currently embarking on a major organizational change, reflecting more participatory structures, more transparent procedures and more modern management approaches that will support not only a more efficient organization but one that is more professional, better capable of detecting and addressing ethical and professional shortcomings among its ranks and better able to respond to the needs of the people, especially victims. A standard lawyer qualification exam has been introduced for every government lawyer. Extensive multi-media public education campaigns have increased the public’s understanding of its rights, the role of the justice system in protecting these rights and what to expect of and require from the justice system.

The changes that have already occurred are too many to list and public perception surveys indicate increased satisfaction with the courts. Significant progress has been made in establishing training, selection, and disciplinary structures where there were none before. Still, these structures and institutions are new and much still needs to be done to strengthen and adjust them to ensure capacities not just for full implementation but rather institutionalization to sustain them over time.

From Law Reform to Organizational Reform

| |

| A meaningful integration of select common law principles is an ongoing experiment and presents a great challenge |

Many

of the newly introduced concepts are still experimental

or evolving. For example, like other evolving democracies

The

Mongolian courts have several components in place that provide

a basis to implement a sound management system. First, each

court has a court administrator responsible largely for

the proper running of the court. Second, the Mongolian courts

are generally well organized despite being significantly

under funded. There is officially no case backlog in

| |

| There is officially no case backlog in Mongolia |

Efficient

court operations contribute to more than timely hearings

and lower costs, they make processes more transparent, hold

participants accountable, and demonstrate to the public

the professionalism of the courts, an important factor in

gaining the public’s trust. Accomplishing changes in court

operations and processes that increase efficiency requires

planning, commitment from the court and changes in the way

the local legal culture views court operations.

Heike Gramckow, Deputy Director, International, National Center for State Courts.